We know that the Darwin Mounds are a unique and diverse place, but the site is large, and there are still areas that we know very little about. One of these areas explored during our expedition is known as the ‘pocket mounds’, just north of the eastern Darwin Mounds field (named like this because they form a small ‘pocket’ of mounds quite distant from the rest of the mounds in the area).

Until a few days ago, this was a relatively unexplored patch of the Marine Protected Area (MPA). On the evening of 20 September, the HyBIS remote underwater vehicle embarked on a mission to collect high resolution video and photographs of these ‘pocket mounds’, and the results were very surprising to the science team.

Fantastically, the ‘pocket mounds’ are home to some beautiful examples of large cold water coral thickets, several metres high and with live colonies of the hard coral species Madrepora oculata and Lophelia pertusa. This is particularly exciting because the eastern area of the Darwin Mounds was the most severely damaged by bottom trawling before the emergency fisheries closure was put in place in 2003. When surveying the area, we found a hugely biodiverse community living amongst the coral mounds, including sponges, anemones, bryozoans, xenophyophores and fish. Perhaps this thriving ecosystem can support the recovery of the coral mounds a little further south by supplying larvae which could attach to pebbles, glacial drop-stones, coral rubble and dead coral framework.

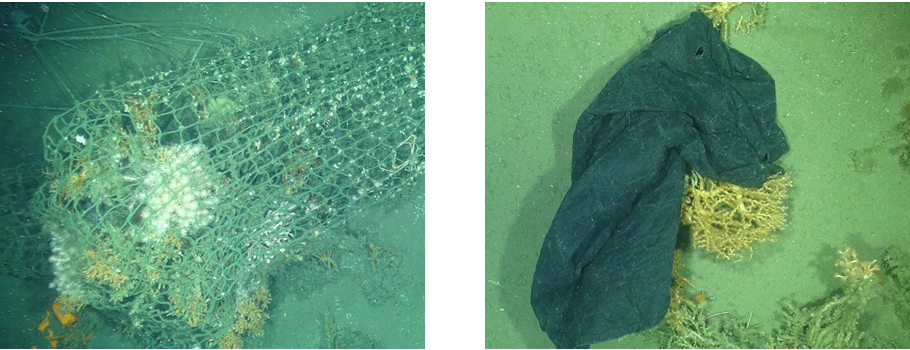

Despite the promising footage of live coral thickets in the pocket mounds, the team were also shocked to see a range of debris strewn over the reefs. Even at more than 1000 metres deep, these communities cannot escape drifting plastic bags and lost fishing nets. The fact that the mounds and coral structures sit a couple of metres higher than the surrounding seabed in an area of strong currents means they are perfect places for marine litter to get snagged. We may have protected these fragile and unique coral mounds from the direct impacts of demersal fishing more than 15 years ago, but some impacts will sadly last for many decades to come. It will be exciting to see how this important ecosystem changes, and hopefully recovers further, in the future.

Written by Hayley Hinchen, Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

Yesterday, this fast and curious pelagic shark (~2 m) inspected HyBIS while she was diving to the bottom. Stay tuned because today is our last HyBIS dive at the #Darwinmounds to explore a site never visited before! @NOCnews @unisouthampton @JNCC_UK @ScotMarineInst @EdinburghUni pic.twitter.com/KVxDrU8xma

— CLASS (@CLASS_UKRI) September 24, 2019